Almost exactly two years ago, I made note of a shocking trend: we were losing 2000s players at an alarming rate. And in the short time since the 2023 season ended, we’ve seen a number of high-profile retirements, which has made me want to look into the matter again.

But first, I wanted to quickly remind everyone of some basics. First, when I refer to “2000s Players”, I’m of course talking about players who debuted between 2000 to 2009, not just “any players who have debuted since 2000”. This topic is kind of a follow-up to something I looked at almost a decade ago, trying to predict who would be the final active player from the 1990s. Once we ran out of 1990s players, it seemed natural to move on to the next decade, so I figured I’d shelve the issue until around 2024 or so.

Except when Buster Posey announced his surprise retirement back in 2021, I began poking around in Baseball-Reference and realized that the topic was coming up on us much quicker than I ever expected. You see, historically, “The Last Active Player from a Decade” has been shockingly predictable:

Last Player from the 1920s: Satchel Paige made it to 1965 if you count his comeback publicity stunt; if you only count regular players, Paige tied with Bobo Newsom (retired 1953)

Last Player from the 1930s: Early Wynn (1963)

Last Player from the 1940s: Minnie Miñoso (1980) if you count his comeback publicity stunts, otherwise Willie Mays (1973)

Last Player from the 1950s: Jim Kaat (1983)

Last Player from the 1960s: Carlton Fisk and Nolan Ryan (1993)

Last Player from the 1970s: Rickey Henderson and Jesse Orosco (2003)

Last Player from the 1980s: Jamie Moyer and Omar Vizquel (2012)

Maybe it’s just me, but I find that stability hilarious: for six straight decades, the last active player would hang up their cleats exactly 24 years after the decade ended. The 1980s saw that slip to 23 years, which is maybe a little unusual, but ultimately not really a meaningful difference.

…Except that, with the benefit of hindsight, maybe it was a sign of things to come? After all of that, our final 1990s players wound up being Adrián Beltré and Bartolo Colon, who both called it quits* after the 2018 season, or five years early if you go by that 24-year rule.

*Technically, Colon would go play in the Mexican League in 2021, but his MLB days ended in 2018.

And if you were hoping that 2000s players might prove to be a rebound here, you’re probably going to be disappointed; for as aggressive as the last decade was at pushing 1990s players out of the league, things are only looking worse for 2000s players this decade. In fact, we’ve generally been a year ahead of the already-accelerated schedule that decade was on:

| Year | Remaining 1990s Players | Remaining 2000s Players |

|---|---|---|

| 2009/2019 | 198 | 134 |

| 2010/2020 | 141 | 82* |

| 2011/2021 | 103 | 72 |

| 2012/2022 | 73 | 42 |

| 2013/2023 | 47 | 24 |

| 2014/2024 | 26 | TBD |

| 2015/2025 | 15 | TBD |

| 2016/2026 | 7 | TBD |

*2020 was obviously affected by the pandemic shortening the season.

And that brings us to the topic that kicked off this article: we’re already down 4 players going into 2024. Miguel Cabrera announced before the season that 2023 would be the end of the road, and since the conclusion of the World Series, Adam Wainwright, Nelson Cruz, and Ian Kennedy have all officially joined him. Going off last decade’s precedent, we can probably expect around another five or so players to hang it up.

And looking over the full list of remaining 2000s players, it’s not hard to find five candidates for those spots. Clayton Kershaw, Daniel Hudson, and Zack Greinke have all publicly expressed uncertainty about returning next year; Kershaw was good enough last year, and Greinke is close enough to 3000 strikeouts, that those two seem unlikely, but I also thought that about Mike Mussina once upon a time, so we can’t take it for granted. Rich Hill has mused about pitching a half-season next year, at 44, and there hasn’t been an update on that front to my knowledge. And there’s no shortage of oft-injured players on that list, who might be privately pondering if it’s worth it to play another season.

Of course, not every player here might get a choice in whether they play next year. No one even tried picking up Madison Bumgarner and his 10.26 ERA after the Diamondbacks cut him in April. Ditto Tommy Hunter (6.85 ERA in 23.2 IP), who the Mets cut in June. And teams always need more pitching, but you have to wonder how many calls Carlos Carrasco and Johnny Cueto will see this winter as free agents in their late 30s, given that both carried ERAs north of 6 last year. Even if they do snag a Spring Training invite, their performance this season definitely casts doubt on whether they actually have enough left in the tank to make a 2024 roster.

Still, it’s difficult to trim down our list too far beyond that; something in the neighborhood of 15 2000s players left sounds about right for 2024. The forecast looks shaky beyond that, but a rapid dropoff at that point would also be right in line with the decline of ‘90s players (who went from 15 to 7 to 3 to 2 over the course of 2015 to 2018).

That would also put us on pace for the final 2000s player stepping off the field sometime in 2027, and honestly, that guess doesn’t feel too off-base. Go back and look at that list I posted, and add 4 years to everyone’s ages; which players do you still see playing then? Our only sub-40 players at that point will be Bumgarner, Kershaw, and Elvis Andrus, meaning our best bet there is the pitcher with the long injury history who’s been going year-to-year on contracts.

Honestly, that’s kind of the recurring problem on our list. The younger half is all somehow more precarious, through injuries, underperformance, or some combination of the two, while the older half generally had a fine 2023 but will need to keep that up until their age 42 or 43 seasons. Ultimately, there are enough good players here, and we only need one to pull through, so saying something like “Max Scherzer retires after his age-42 season” or “Clayton Kershaw holds it together long enough to reach 2027” doesn’t seem too crazy.

But man, does predicting even one extra year on top of that feel unlikely; remember, 2017 is still one year less far-out comparatively than 1990s players made it with Beltre and Colon. And the final representatives of all the decades before then made it over half a decade on top of that. How did they even do that? It seems unthinkable in the modern context.

Something must have changed, right? Like, bad timing could explain a little bit of variation between the 1990s crop of players and the 2000s one, but that still doesn’t account for all of the decades before that. And you can point to steroids, but again, this is a trend that goes all the way back to players who debuted in the 1920s, so there had to also be some sort of non-steroid factor in play as well.

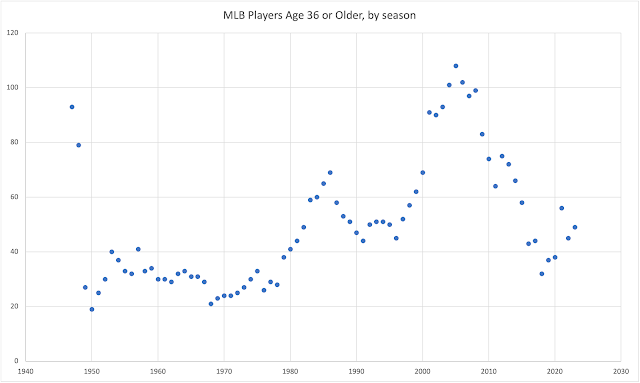

At this point, I figured it might be good to actually put numbers to it, to get a better sense of the overall trends we’re seeing. So I used Baseball-Reference to get a count of the number of players 36 or older who played in every season dating all the way back to the start of integration in 1947. The results are pretty striking:

As you can see, after two high counts due to the larger number of teams (the Negro Leagues were granted Major League status only through 1948, meaning there were 28 teams being measured for those two season), the number of active older players basically stays in the 20 to 40 range for three decades. Even the extra roster spots from eight new teams being added to the league in the 1960s didn’t really open any doors for older players right away.

Of course, it takes off after that throughout the 1980s, dips slightly and plateaus in the 1990s, and then peaks for the entirety of the 2000s. We then drop steeply into the range we saw in the ‘80s and ‘90s, bottoming out in 2018 before rebounding back into that wide “40-80” range. Of course, these are all raw numbers; if you want to adjust based on the number of available roster spots, we’re seeing a rate much closer to the 1970s and very early ‘80s.

So that’s part of our answer: we actually are seeing a decrease in old players, compared to the last few decades. And it kind of naturally follows from there, the fewer 36 year olds in the league, the lower the odds that at least one of them will play significantly more time. Of course, there’s still a missing part of the equation here; we’re at the lowest point for old players we’ve been in four-to-five decades, but the last time we were this low (and even before that, when we had even fewer old players) we still regularly saw at least a few players make it 24 or 25 seasons.

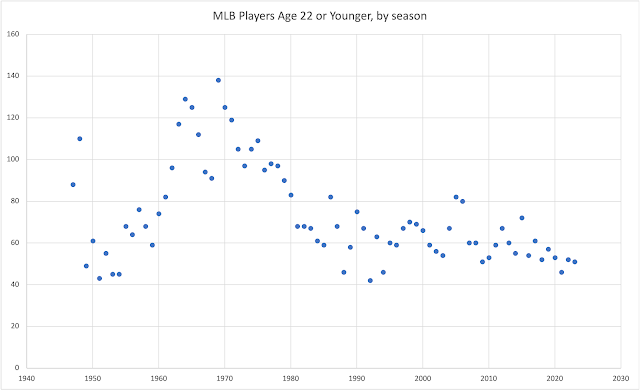

Of course, maybe you’ve already figured out the other half of this puzzle. Players in the 1960s and ‘70s weren’t generally playing as much into their late 30s and early 40s, but they were starting earlier. As evidence, here’s the number of players in every season younger than 23, once again since the start of the integration era:

The decline has been much more gradual compared to the decline of old players, but it’s pretty undeniable. This isn’t the worst time ever for super-young players, but it’s maybe just one tier above “the worst time”. But of course, once again, this is in spite of the greater number of teams and roster spots; if you go just on a players-per-team basis, 2023, 2022, and 2021 have in fact been (respectively) the fourth-worst, sixth-worst, and worst seasons in Major League history.

So players are getting called up later, and retiring earlier. Add those two sides together, and we’re seeing a lack of extreme players at either end not seen since basically the 1950s; of course, the ‘50s managed this total with roughly half of the roster spots that exist today. If you want a visual look at those trends:

Of course, “fewer young players and fewer old players” explain the issue somewhat, but not entirely, not to mention that it doesn’t really explain why we’re seeing this trend. Of course, on both accounts, there are some pretty obvious culprits at play here, including: the greater focus on player development delaying young stars in the minors rather than calling them up right away; the greater prevalence of steroid testing likely disproportionately affecting older players; growing concerns of injuries for young pitchers who throw a lot of innings at a young age; larger contracts offering players enough money to feel comfortable walking away earlier than they may have felt in an earlier era; and the optimization of roster construction that emphasizes cheap younger players over more expensive veterans, while also trying to delay those young players’ service time to maximize peak seasons before free agency.

I don’t know that I can say how much each of these factors contributes to the issue of fewer long-running major league stars, but I’m also not sure how much it matters? There’s definitely not the sort of widespread discontent with the issue in fan circles, at least, not in the way we saw with something like, the lack of balls in play. And even if it was a bigger issue for fans, a lot of these factors can’t be tweaked anyway, or to the extent that they can, then certainly not as easily as enforcing a pitch clock or banning the shift.

The one change that I might see affecting this is an expansion; our current run of 25 years with 30 teams is far and away the longest Major League Baseball has held a status quo since… I suppose from the expansion of the AL in 1901 to the first MLB expansion in 1961? Of course, even that era saw turnover in top-level team counts outside of MLB, between things like the experiment of the Federal League, or the turnover in Negro League teams. And of course, every other sports league has now expanded to 32 teams, not to mention that overall population growth in that time means an expansion would probably be justified.

Perhaps a sudden flood of new roster spots would change how front offices value those spots, and inspire teams to bring back a few older players, or try a few more young players to fill things out? But I’m not even sure of that; teams might just decide they’re better off going with even more 24-to-30 year old AAA players, rather than risk giving those spots to unproven younger rookies, or trying to squeeze more on an older veteran. I suppose we won’t really know the specifics of how these roster decisions will play out until expansion happens on its own (which I do think will happen eventually, although I couldn’t begin to guess at the owners’ timeframe here).

Of course, that’s all long-term; discussion of expansion teams seem to be confined to whispers while the league tries to deal with moving the A’s (and then perhaps the two Florida teams? Who really knows what their plans are...). One day it might change, but it’s not going to happen in time to extend the careers of any 2000s players; look for the best contenders for the Last Player to assert themselves in 2024 and 2025, and for the issue to be resolved in the next four years or so.

Tommy Hunter has officially announced his retirement, meaning we are now under 20 players. https://www.mlbtraderumors.com/2023/12/tommy-hunter-officially-retires.html

ReplyDelete